Many teams “manage” technical debt successfully and still lose agility.

They allocate 20% of capacity to tech debt work. They run periodic “cleanup sprints.” They have refactoring tickets in their backlog and occasionally prioritize them. By most measures, they’re doing the responsible thing.

These are not negligent teams. By conventional standards, they’re doing exactly what we recommend.

And yet their capacity to change continues to erode.

The technical debt simulator reveals why. Different refactoring strategies that invest the same total effort produce radically different outcomes. The difference isn’t how much you invest. It’s when and how you invest it. This is the second article in a series on technical debt and change capacity. The first article established why output metrics hide capacity collapse. This one separates debt containment from capacity preservation, and shows why continuous refactoring isn’t just better practice but mathematically cheaper.

Same effort, radically different outcomes

Run any two presets in the simulator with the same time horizon and the same structural drag. The total effort is always 52 weeks. The underlying friction rate is identical. Only the strategy parameters vary.

This is the controlled comparison that matters. Not “should we refactor more or less?” but “given the same investment, which approach delivers more while preserving more capacity?”

The experiment isolates strategy from effort. Same inputs, different allocation patterns. If you’re a CFO looking at engineering ROI, this is the only comparison that matters. If you’re a CTO explaining why refactoring discipline isn’t optional, this is the evidence that ends the debate.

The answer is unambiguous once you see the curves.

Continuous refactoring delivers 38.0 weeks of changes over the year. Adaptive delivers 35.4. Monthly periodic delivers 35.0. Baseline (no refactoring) delivers 30.7.

Backloaded refactoring? 20.3 weeks.

Same effort. Same starting conditions. Continuous refactoring nearly doubles delivered output compared to deferral.

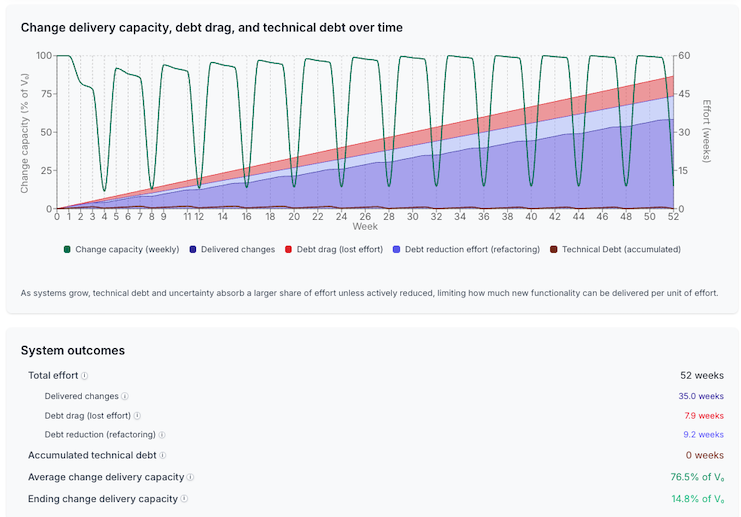

Periodic refactoring: batching by another name

Monthly, quarterly, and annual cleanup schedules all belong to the same class of strategy. The frequency changes how the pain is felt, not whether it exists. Run the Monthly Refactoring preset. The team alternates between feature development and cleanup on a monthly cadence, with most refactoring periods dedicated to debt reduction.

The visual pattern is unmistakable: oscillating capacity. During development phases, debt accumulates and effective change capacity drops. During cleanup phases, capacity recovers as debt is paid down. Over time, the system avoids runaway debt, but only by repeatedly swinging between buildup and recovery.

Delivered changes: 35.0 weeks. Debt drag: 7.9 weeks. Debt reduction effort: 9.2 weeks.

The important insight isn’t the ending capacity snapshot. Because the model ends on a refactoring phase, the final capacity appears artificially low. What matters is the shape of the curve.

Monthly refactoring creates a whipsaw system. Teams are most productive right after cleanup. Least productive right before the next cleanup. And always paying interest during the build-up phase.

The debt is controlled, but never eliminated. Every development phase intentionally carries drag. Every cleanup sprint is paying interest on time borrowed earlier. The team achieves stability, but at a permanent efficiency penalty.

Shorter batches reduce the amplitude of the swings. Weekly cleanup is better than monthly. Monthly is better than quarterly. But all batching still loses to continuous flow because batching itself creates the interest-bearing interval. Periodic refactoring is not irresponsible. It works. It’s just more expensive than it needs to be.

This is exactly what Bèr Kessels describes with compound interest on technical debt: even when debt is serviced, allowing it to accumulate between payments guarantees higher total cost than paying continuously.

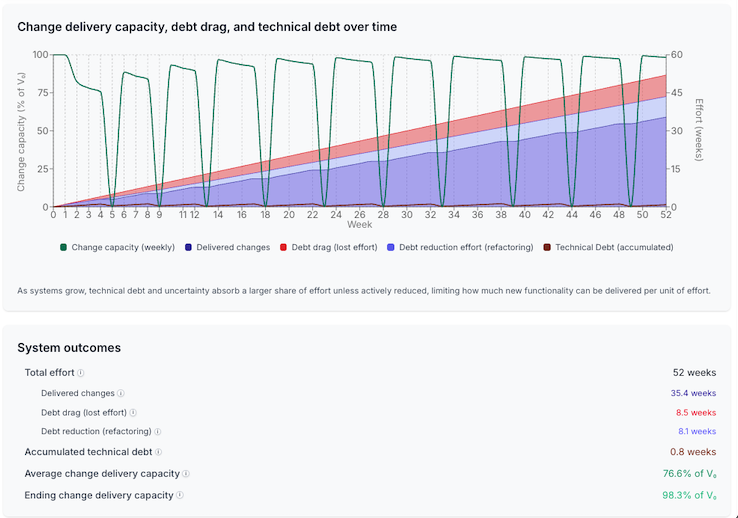

Adaptive refactoring: smart deferral

The Adaptive preset represents a more sophisticated approach. The team sets a debt threshold (in this case, 1 week of accumulated debt) and triggers cleanup only when that threshold is exceeded. It’s responsive rather than scheduled, intelligent rather than rote.

The results are better than periodic but worse than continuous.

Delivered changes: 35.4 weeks. Debt drag: 8.5 weeks. Debt reduction effort: 8.1 weeks. Accumulated debt: 0.8 weeks. Ending change delivery capacity: 98.3% of baseline.

That ending capacity number looks reassuring. But look at the delivered changes: 35.4 weeks versus 38.0 weeks for continuous. Same effort, different allocation, measurably less output. The adaptive approach bounds debt effectively. It maintains capacity. But it allows debt to accumulate up to the threshold before acting, which means the team always carries some drag. That residual drag accumulates into lost output over time.

There’s also a hidden cost: decision overhead. The team has to monitor debt levels, evaluate when thresholds are crossed, and context-switch between development and cleanup modes. That coordination friction doesn’t show up in the simulator but shows up in reality.

Adaptive refactoring is smart deferral. It responds to actual conditions rather than arbitrary schedules. But as long as debt exists, interest is being paid.

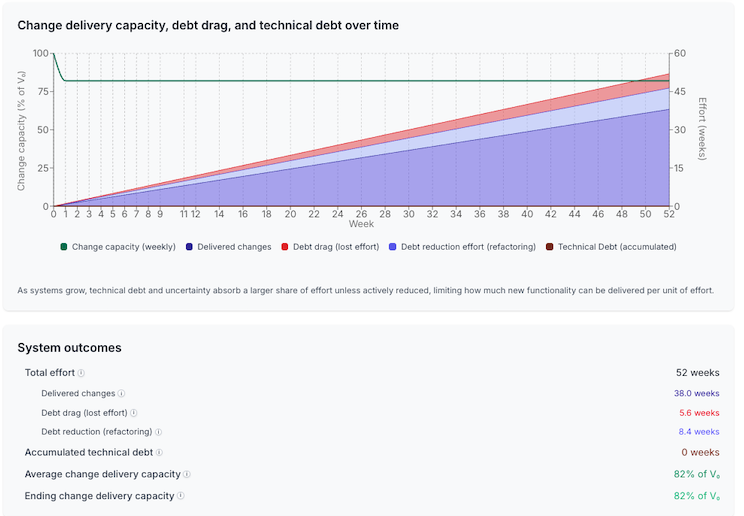

Continuous refactoring: the invariant

The Continuous preset allocates 18% of effort to ongoing debt reduction, integrated into every development cycle.

It’s worth being explicit about the tradeoff. Continuous refactoring never reaches the dramatic peaks that periodic and adaptive strategies do. It doesn’t hit 95% or 100% change delivery capacity after a cleanup phase. Instead, it holds a steady line at roughly 82% throughout. That can feel like a loss. An 18% reduction, forever, looks expensive, especially when other strategies briefly touch near-perfect productivity.

The visual is striking: a flat capacity line. The change delivery capacity stays constant at 82% of theoretical maximum throughout the entire year. No oscillations. No degradation. No recovery phases because

Delivered changes: 38.0 weeks. Debt drag: 5.6 weeks. Debt reduction effort: 8.4 weeks. Accumulated debt: 0 weeks. Ending change delivery capacity: 82% of baseline.

The difference is that those peaks are a mirage. Monthly and adaptive strategies oscillate between highs and lows. They feel fast right after cleanup, then steadily slow as debt accumulates. The visible peaks are paid for by equally real troughs. What matters over a horizon isn’t the maximum capacity reached in a good week. It’s the average capacity sustained and the total change delivered.

Continuous refactoring gives up the illusion of occasional 100% weeks in exchange for something far more valuable: consistent, predictable delivery at a level that never collapses. The seductive part of periodic and adaptive refactoring is how productive they feel at their best. The cost is how much time they spend paying for it.

Zero accumulated debt. The capacity cost of the ongoing investment is more than offset by the eliminated drag.

Dave Farley uses a restaurant kitchen analogy in Modern Software Engineering. A professional chef doesn’t skip cleaning because they’re busy. The cleaning is the work. It’s what allows them to cook fast, consistently, and safely. The continuous approach treats refactoring the same way: not separate from development, but part of development. The boundaries between “feature work” and “cleanup work” blur because the team maintains cleanliness as a constant discipline rather than a periodic intervention.

Continuous refactoring isn’t more virtuous. It’s cheaper.

Continuous refactoring restores forecastability

One of the least discussed costs of technical debt is what it does to planning.

When capacity oscillates, forecasts become fiction. Roadmaps slip not because teams are bad at estimating, but because the underlying system keeps changing its behavior. A plan made at 90% capacity silently degrades into execution at 40%. By the time anyone notices, the miss is already locked in.

Continuous refactoring changes that.

By holding change delivery capacity stable, it gives teams something rare in software: a surface you can plan against without lying to yourself. Not perfect predictability, because software work is inherently uncertain, but predictable capacity behavior. You can’t forecast what will happen exactly, but you can forecast how the system will respond.

That distinction matters.

With continuous refactoring, future work doesn’t depend on a fragile assumption that “things won’t get worse.” You can sequence initiatives, make commitments, and reason about tradeoffs knowing that capacity won’t quietly erode underneath you. The system may surprise you, but it won’t betray you.

Periodic and adaptive strategies never offer that confidence. They create bursts of optimism followed by slow decay. Plans made at the peak fail in the trough. Over time, teams stop trusting their own forecasts, and organizations respond by adding buffers, process, and approval layers, further increasing drag.

The stable, boring line isn’t just cheaper. It’s governable. That’s the real advantage of continuous refactoring: it turns change capacity from a fluctuating variable into a dependable constraint. And once capacity is dependable, strategy becomes possible.

AI amplifies volatility and rewards stability

Layer AI-accelerated development onto these strategies and the differences amplify.

Periodic refactoring with AI assistance produces deeper troughs. Development phases generate more debt faster, overwhelming the cleanup phases. The oscillations become more violent, the recoveries less complete. AI compresses the compounding cycle: in an AI-accelerated codebase, a month of debt accumulation can exceed what manual development produced in a quarter, and the cleanup sprint arrives too late to recover.

Adaptive refactoring with AI becomes constant firefighting. The thresholds are crossed more frequently. The team spends more time evaluating debt levels and triggering cleanup cycles. The decision overhead scales with velocity.

Continuous refactoring with AI produces sustained acceleration. The flat capacity line holds. The team absorbs the increased velocity without destabilizing because they never allow debt to accumulate.

This connects to what the 2025 DORA Report found: AI magnifies whatever already exists in your organization. Strong foundations see acceleration. Fragmented processes see their dysfunction multiply.

Continuous refactoring is the only strategy that preserves a stable invariant under increased velocity.

The kitchen test

Two restaurant kitchens. Same menu, same staff skill, same hours.

Kitchen A cleans as they cook. Every station maintains its workspace. Pans get washed during natural pauses. The kitchen never accumulates mess.

Kitchen B prioritizes output. Chefs stack dirty equipment for “later.” Once a week, the whole team stops cooking and spends a few hours cleaning.

At first, Kitchen B looks faster. By month three, Kitchen B is slower. The accumulated grease makes equipment harder to clean. The piled dishes block access to tools. Chefs spend time hunting for clean equipment instead of cooking.

Kitchen A serves more meals per year. Kitchen B has more dramatic “cleaning sprints” but worse cumulative output. The mess doesn’t just slow the cooking; it taxes the cooks. Engineers working in accumulated debt spend cognitive effort navigating complexity instead of solving problems.

The simulator runs this experiment with math instead of grease. The outcome is identical.

Stop debating quantity

Most refactoring discussions focus on the wrong question. “How much refactoring is enough?” assumes that refactoring is a budgeted activity separate from development, a tax you pay to maintain a healthy codebase.

That framing leads to periodic strategies: allocate X% to tech debt, schedule cleanup sprints, measure refactoring velocity separately from feature velocity.

The simulator shows why this framing fails. The question isn’t quantity. It’s cadence. When you refactor matters more than how much you refactor.

Continuous approaches integrate refactoring into the development flow. There’s no separate bucket for “tech debt work” because every development cycle includes appropriate cleanup. The discipline is baked into how the team works, not scheduled as a separate activity.

This is a systems choice, not a resource allocation choice. You’re not deciding how much to invest in refactoring. You’re deciding what kind of development process you want: one that accumulates debt and periodically pays it down, or one that maintains cleanliness as an invariant. Maintaining the invariant is cheaper than paying the interest. The simulator makes that unavoidable.

In the final article, I’ll explore what continuous refactoring can’t fix: structural drag. Refactoring manages accumulation, but baseline friction is set by architecture, tooling, team structure, incentives, and ways of working. That’s where the real leverage lives.