You cannot refactor your way out of a bad structure.

The previous articles, Why shipping faster makes teams slower and Why most teams refactor correctly and still lose showed how technical debt compounds to erode change capacity, and why continuous refactoring outperforms periodic cleanup strategies. But those articles assumed a fixed structural drag, the baseline friction rate that affects all work regardless of how well you manage debt accumulation.

Structural drag determines the ceiling for every strategy you employ. And unlike accumulated debt, you can’t clean it up with refactoring sprints.

Most orgs do the opposite: they push velocity first, then argue about refactoring, and only touch structure when the system is already expensive to change.

This is the final article in the series. It shows why structure: architecture, practices, and organizational design matters more than discipline, and why most organizations get the leverage ordering exactly backwards.

Structural drag is the tax rate on all future work

The technical debt simulator models structural drag as a baseline parameter. The default is 10.8%, representing a relatively healthy but non-greenfield system. Empirical studies often measure 20-30% productivity loss in mature systems.

This number represents the friction that exists before any debt accumulates. It’s the architectural complexity, the coupling between components, the deployment friction, the observability gaps, the organizational boundaries that force coordination.

You can’t refactor it away. You can’t sprint harder. You can spend more on cleanup, but it won’t lower the baseline friction.

Think of it as a tax rate. Every hour of engineering effort gets taxed by this rate. A team with 10% structural drag converts 90% of effort into potential progress. A team with 25% structural drag converts only 75%. It’s a simplification, but it matches how friction behaves in practice: it taxes every change.

The difference compounds across every sprint, every quarter, every year. The team with lower drag doesn’t just work more effectively. They accumulate less debt per unit of output, recover from mistakes faster, and maintain capacity longer.

Lower drag lifts every curve

Run any preset in the simulator, then reduce the structural drag slider. Watch what happens to the outcomes.

Every curve lifts. Every strategy improves. The relationships between strategies remain the same: continuous still beats periodic, periodic still beats deferred. But all of them perform better with lower baseline friction.

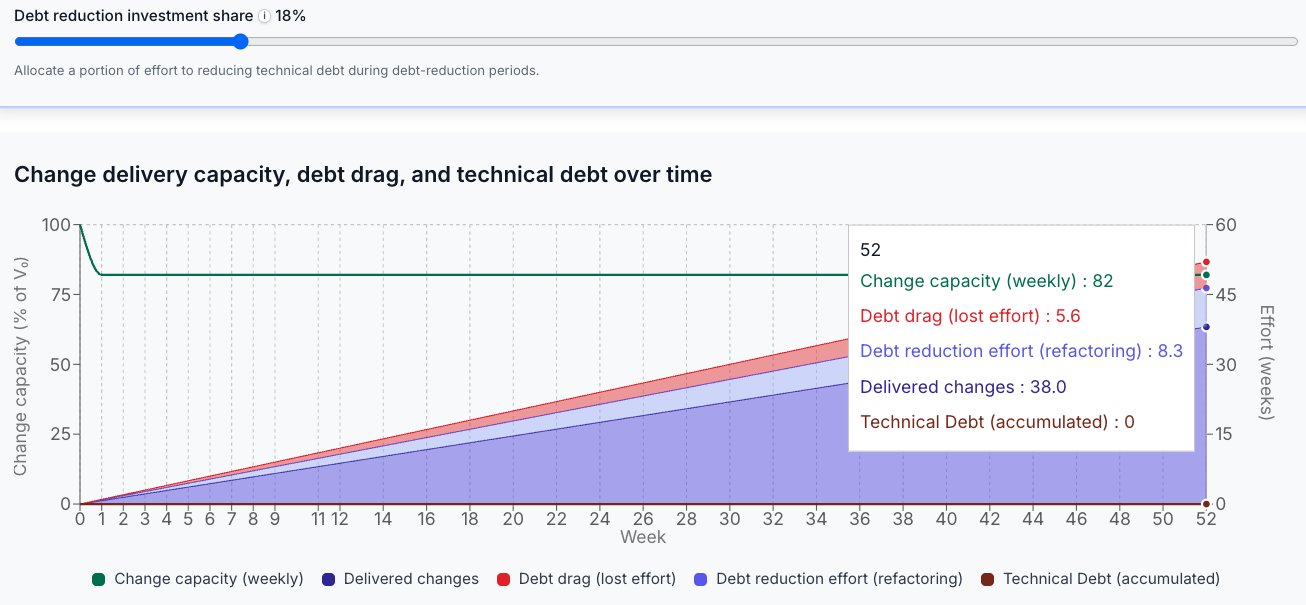

At 10.8% drag with continuous refactoring and 18% cleanup investment, delivered changes hit 38.0 weeks.

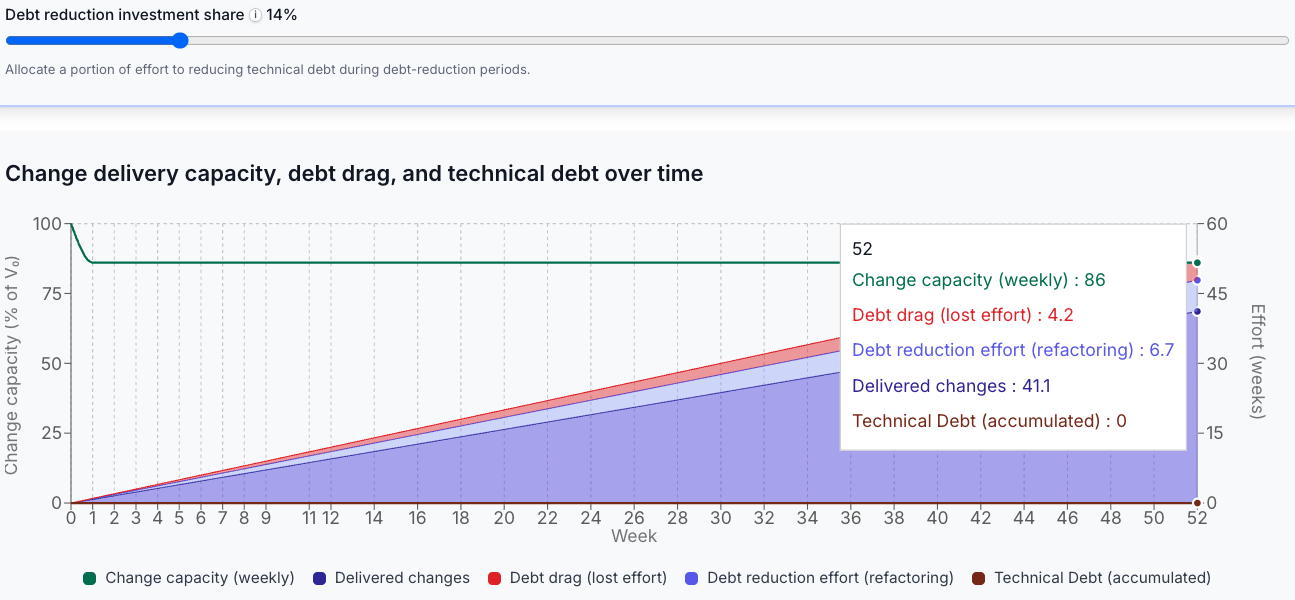

Drop drag to 8% and the system needs less maintenance to stay clean: you can cut cleanup to 14% and still deliver 41.1 weeks with zero debt.

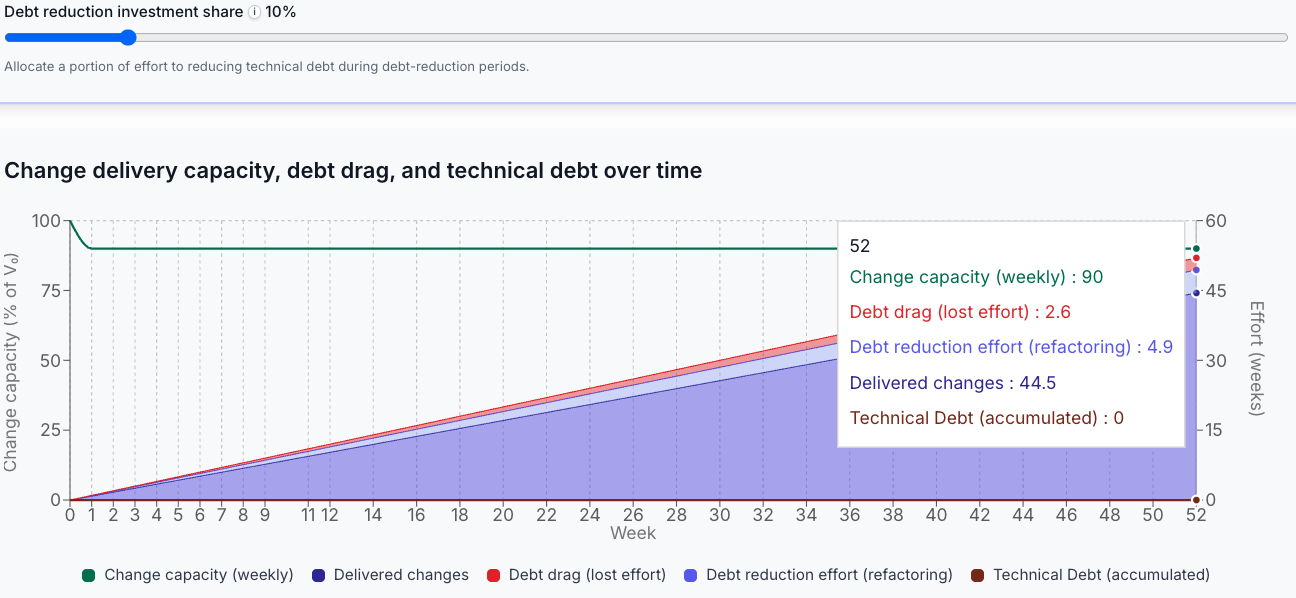

Drop to 5% drag and cleanup investment drops to 10%, yielding 44.5 weeks of delivered changes.

Same team. Same horizon. Less drag means you buy back both output and maintenance headroom.

The improvement is multiplicative across time. Lower drag means less debt generation per cycle, which means less refactoring required, which means more capacity for new work, which compounds forward.

More striking: at lower structural drag, the gap between strategies narrows. When the baseline friction is low enough, even suboptimal strategies produce acceptable results. High friction environments punish mistakes severely. Low friction environments are forgiving.

This is why some organizations can get away with practices that would destroy others. They’re not smarter about debt management. They’ve made structural choices that lower the tax rate on all their work.

High drag makes discipline barely sufficient

Numbers below are from the simulator under the same horizon and model assumptions used throughout this series; treat them as directional economics, not a prediction for your specific org.

Flip the experiment. Increase structural drag to 20%.

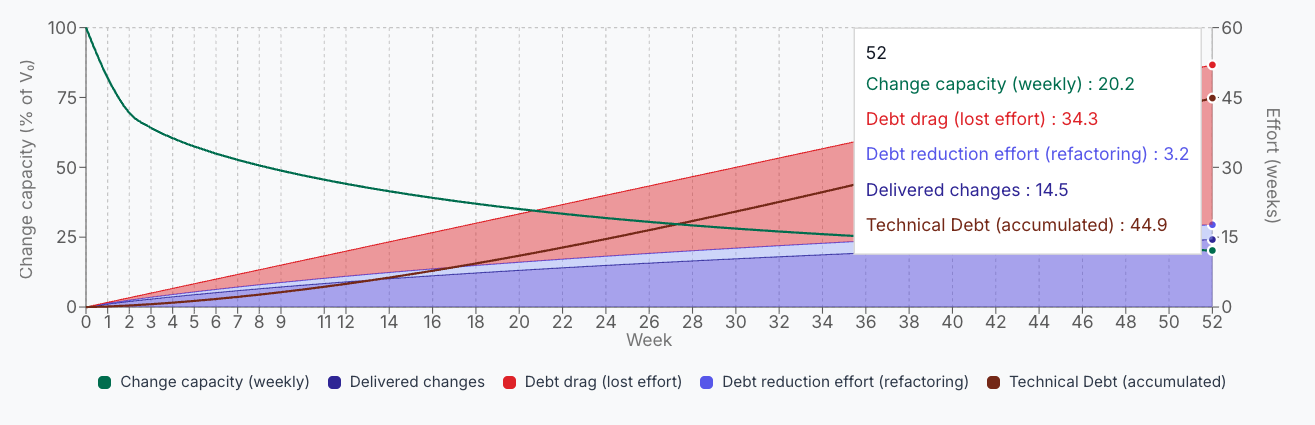

Now watch the continuous refactoring strategy struggle. With the same 18% cleanup investment, the team delivers only 14.5 weeks of changes over 52 weeks and accumulates 44.9 weeks of debt. The discipline that worked at 10.8% drag is overwhelmed at 20%.

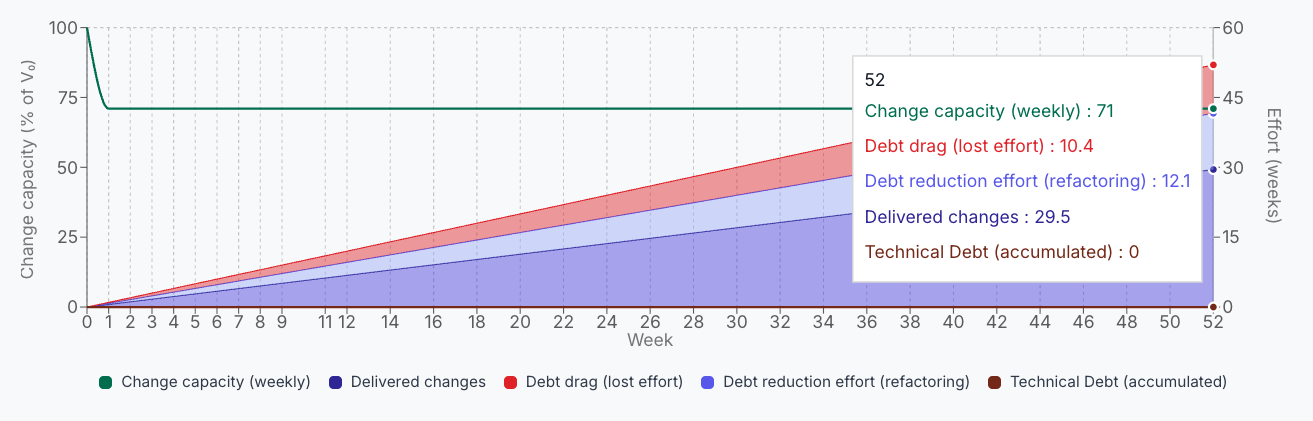

To maintain zero accumulated debt at 20% drag, you need to raise cleanup investment to 29%. Even then, you only deliver 29.5 weeks of changes. Nearly a third of all effort goes to maintenance just to stay even.

At high drag, you’re not just paying time; you’re paying attention. Teams burn cognitive budget navigating the system instead of solving the problem.

The baseline scenario is worse. At 20% drag with no refactoring, capacity drops below 50% by week 5. At that point, the project is effectively unrecoverable on product timelines. To eliminate all accumulated debt by year end, you’d need to shift entirely to cleanup by week 13 and spend the remaining 39 weeks doing nothing but paying down debt.

That’s not a refactoring strategy. That’s a rescue operation.

Under AI-accelerated development, these dynamics compress. The timeline to collapse shortens. The window for intervention narrows. Teams that barely managed with manual development velocity find themselves underwater with AI-assisted output.

High structural drag doesn’t just make work harder. It makes discipline insufficient. No amount of refactoring effort can overcome a fundamentally friction-heavy system.

What actually lowers structural drag

Structural changes are harder than refactoring because they cross boundaries. They require coordination across teams, agreement on interfaces, investment in infrastructure that spans organizational silos. Some require changing how people work together, which is harder than changing code.

The interventions fall into three categories: technical architecture, engineering practices, and organizational design. Most teams focus on the first and ignore the other two. That’s a mistake, because each category addresses a different surface area of drag.

Technical architecture makes it safer to deploy and operate. Engineering practices make it safer to develop and iterate. Organizational design makes it easier to ideate and collaborate. You need all three.

Technical architecture

Decoupling reduces structural drag by localizing the blast radius of changes. When components are loosely coupled, modifications to one don’t cascade through the system. Testing becomes faster. Deployments become safer. Teams can move independently.

This doesn’t necessarilly mean microservices. A well-structured modular monolith can achieve strong decoupling without the operational overhead of distributed systems. Premature microservice proliferation often increases structural drag by adding network boundaries, deployment coordination, and distributed debugging complexity. The goal is logical separation with clear interfaces, not physical separation for its own sake.

Decoupling contains debt to subsystems. When shortcuts can’t spread across boundaries, the interest doesn’t compound across the entire codebase.

Deployment friction reduction lowers drag by making change cheap. But it’s not enough to have CI/CD pipelines. You need pipelines that always work. Flaky tests, unreliable builds, and deployment processes that require manual intervention all add friction that taxes every change.

The discipline matters as much as the tooling: pipelines that break get fixed immediately, tests that flake get quarantined or deleted, and the path from commit to production stays fast and reliable. Feature flags, canary releases, and automated rollbacks reduce the risk of each deployment, which allows smaller changes, which compounds into less accumulated complexity.

Observability reduces drag by shortening feedback loops. When teams can see what their changes do in production, they catch problems faster, debug more efficiently, and build confidence in their modifications. Poor observability forces defensive coding, extensive manual testing, and cautious deployment strategies.

Platforms that surface cycle time, deployment frequency, change failure rates, and flow metrics make structural drag visible. You can’t improve what you can’t see. The value isn’t in the dashboards themselves but in exposing where friction lives so you can target interventions.

Engineering practices

These aren’t “process improvements.” They change the system’s feedback loops and coordination cost, the structure that determines drag.

This is where most organizations try to substitute tooling for discipline. Some of the highest-leverage structural improvements aren’t tools or architecture. They’re disciplines that many teams resist.

Trunk-based development reduces drag by eliminating long-lived branches. Feature branches create integration debt that compounds until merge day. Trunk-based development forces continuous integration, which surfaces conflicts early when they’re cheap to resolve. The practice feels risky until you realize that the alternative, big-bang merges, is where the real risk accumulates.

Test-driven development reduces drag by building verification into the development cycle. The insight isn’t about test coverage. It’s about design pressure. TDD forces you to write code that’s testable, which means code that’s decoupled, which means code that accumulates less structural debt.

Pairing and mobbing reduce drag by distributing knowledge across the team. Collaborative programming eliminates the single points of failure that create coordination bottlenecks. When everyone understands the system, changes don’t wait for the one person who knows that module.

Small batches and WIP limits reduce drag by keeping work flowing. Work in progress is inventory, and inventory is waste. Teams that limit WIP and work on one thing at a time spend less effort on context switching and coordination. The batch size is a structural choice that affects the tax rate on all future work.

These practices are harder to adopt than buying a platform or refactoring a module. They require changing habits, challenging assumptions, and accepting short-term discomfort for long-term gain. That’s why most teams avoid them.

Organizational design

Team boundaries are structural choices with the same compounding effects as architectural boundaries. A team structure that forces coordination is a tax rate, just like a tightly coupled codebase.

Conway’s Law says systems mirror the communication structures that build them. If your architecture is tangled because your org chart forces artificial boundaries, no amount of technical refactoring will untangle it. You have to change how teams interact.

Team Topologies provides patterns for this: stream-aligned teams, platform teams, enabling teams, and complicated-subsystem teams. Org Topologies extends this by examining how organizational structure affects adaptability at scale, mapping the progression from specialized silos with heavy coordination overhead, to cross-functional teams that can deliver independently, to fully integrated units that combine discovery and delivery without external dependencies.

The pattern is consistent: structures that force coordination across boundaries create friction. Specialized teams optimized for utilization burn capacity on handoffs and approvals. Cross-functional teams remove technical bottlenecks but still coordinate at feature boundaries. Fully integrated teams eliminate both by owning end-to-end value streams without crossing organizational seams.

The ability to change direction quickly and safely depends on organizational structure as much as technical structure. Teams that share context and can collaborate without heavyweight coordination processes operate with fundamentally lower friction. This connects directly to cognitive load: every unnecessary boundary, approval process, or coordination requirement adds extraneous load that taxes the capacity available for actual problem-solving.

Lower structural drag isn’t just about faster systems. It’s about shared understanding: teams that can see, reason about, and safely change the system with minimal coordination overhead.

How organizations apply leverage backwards

Here’s how leverage actually stacks:

- Structural drag (the tax rate)

- Refactoring discipline (accumulation control)

- AI augmentation (output multiplication)

The highest leverage intervention is reducing structural drag. Every point of friction you remove lifts every strategy, every team, every project. The benefits compound indefinitely.

The second highest leverage is refactoring discipline. Continuous approaches prevent accumulation, preserve capacity, and maintain adaptability. But they operate within the ceiling set by structural drag.

The lowest leverage is AI augmentation. AI tools multiply output but don’t change the underlying economics. If your structure is high-drag and your discipline is weak, faster output just accelerates your collapse.

Most organizations invert this ordering. They invest in AI tools and more engineers while deferring discipline and neglecting structure.

They’re accelerating toward a wall they could have moved.

Teams with loosely coupled architectures, strong engineering practices, and fluid organizational structures see AI multiply their effectiveness. Teams with tightly coupled systems, weak practices, and rigid hierarchies see AI multiply their dysfunction. The structural choices determine whether augmentation amplifies or overwhelms.

Why structural changes are resisted

If structural changes offer the highest leverage, why don’t organizations prioritize them?

The benefits are diffuse and delayed. Lower coupling doesn’t show up as a line item. Better pipelines don’t demo well. Fewer handoffs don’t make a compelling roadmap slide.

The costs are concentrated and immediate. Structural work forces cross-team coordination, threatens local optimizations, and competes directly with feature throughput.

So most organizations do the rational thing under their incentive system: they buy velocity and postpone leverage. Then they act surprised when the system gets harder to change.

This is why technical due diligence focused on adaptability matters more than traditional architecture audits. Investors who evaluate only current code quality miss the structural dynamics that determine whether a company can keep evolving. The same logic applies internally: leaders who measure only output miss the structural investments that determine whether output can be sustained.

McKinsey’s research on technical debt shows this pattern clearly: organizations treat modernization as a project rather than a continuous investment. They defer structural work until it becomes unavoidable, then execute expensive transformation programs that could have been prevented by steady investment in architecture.

Refactoring is table stakes, not strategy

Refactoring discipline isn’t a strategy. It’s the minimum viable practice for not going backwards.

Continuous refactoring prevents accumulation. It maintains the capacity you have. It keeps you from drowning. That’s necessary. It’s not sufficient.

Strategy is about bending the curve, not just managing the decline. Strategy asks: how do we lower the structural drag that determines our ceiling? How do we make the system more adaptable, more responsive, more capable of change?

The teams that answer those questions, that invest in decoupling, observability, deployment infrastructure, and organizational flow, gain compounding advantages. Their competitors fight to maintain capacity. They compound capability.

The investment question

Technical debt is inevitable. Entropy is real. Markets shift. Systems accumulate misalignment between what they can do and what the business needs them to do.

But fragility is a choice. Structural choices determine whether debt compounds against you or for you. Refactoring discipline determines whether accumulation overwhelms capacity or stays bounded.

Here’s the question every leader should ask: if reducing handoffs, shortening feedback loops, and decoupling work so teams can change independently could raise delivered output ~17% without adding headcount, would you make that investment? In high-drag environments, the difference is even starker: it’s the gap between “manageable” and “rescue operation.”

The simulator shows the math. Dropping structural drag from 10.8% to 5% increases delivered changes from 38 weeks to 44.5 weeks with the same team over the same horizon. That’s a 17% improvement in output from structural investment alone, with lower cleanup overhead and zero accumulated debt.

The interventions that produce these results aren’t expensive in dollars. They’re expensive in comfort. They require changing how people work, challenging assumptions about branching strategies and testing practices, and reorganizing teams around flow rather than function.

The math doesn’t care about organizational politics. The teams that make structural investments compound capability. The teams that defer them compound drag.

The question for every organization is the same: are you investing in the leverage that compounds, or the velocity that hides constraints until it’s too late?

Article 1 showed how output can look healthy while capacity collapses.

Article 2 showed that cadence is economics: continuous refactoring is cheaper than periodic cleanup.

This article is the final lever: lower the baseline friction. Refactoring keeps you from going backwards. Structure determines whether “stable” is merely survivable, or strategically fast.

This article is part of a three-part series on technical debt, refactoring strategies, and structural drag. The technical debt simulator is available free at arielperez.io.